A lot of what the Consumer Duty is about is ensuring that clients are empowered to make better financial decisions.

There’s a fundamental tenet here – it’s not enough that they have you as their advice professional. They have to understand things for themselves. They don’t need to understand Markovitz and modern portfolio theory. They don’t need to be tax experts. They don’t need to be you. But we have to make sure they understand what’s going on.

To ensure that clients are empowered to make better financial decisions, we need to be able to draw a distinct, ink black solid line from a client’s objectives, circumstances and goals into the regulated CIP that we’re using.

Too many firms aren’t acting as they should, though I don’t think it’s anyone reading this. Most firms are righteous and are trying to do the right things for clients, often in difficult circumstances with competing pressures and information coming at you in real time.

There are four Consumer Duty outcomes, which are probably now revision for you at this stage: consumers should receive communications they can understand, products and services that meet their needs, offer fair value, and offer the support they need. We’ll spend some time on what this all really means in the context of equipping consumers to make effective financial decisions.

The meaning of ‘fair value’

Let’s start with products and services that deliver fair value – there’s a basket of frogs straightaway.

What is fair value? I don’t know. Do you know? No, you don’t. And the reason you don’t know is that value is ascribed by an individual to a product or service based on their experience of it.

For them to ascribe value, they must understand two things. They must understand what the product or service is and what it does, and they must understand what it costs. There’s no point an individual having a big rectangular cuboid metal box in their kitchen, and they pay £250 for it, and it just sits there because nobody told them it was a fridge.

As advisers and planners, you are allowed to have a sense of what fair value is on behalf of clients, and you exercise that all the time. But it must be on behalf of clients. That’s quite important.

In any debate about value, somebody usually pipes up to say: “It’s the price of everything and the value of nothing” – like you’ve actually read Oscar Wilde, which you haven’t. Or: “Price is not the same as value.” It’s true that price isn’t the same as value, but price is a fundamental component of value. And we need to get both parts right in order to understand them.

Consumer support and helpful customer service

Under Consumer Duty, it should be as easy to switch, cancel or complain as it was to buy the product or service. Now, I used to work in big providers before I started doing the thing that I’m doing now. I got fired quite a lot and eventually took the message.

But if I’d gone into my bosses and said: “Hey, I’ve got this killer idea. I want £5m to build the best team in the industry to make sure money leaves us as quickly as it possibly can,” how long do you think I would have lasted? The answer is about as long as I lasted anyway, but just for different reasons. The point is, making switching, cancelling or complaining easier represents a huge shift.

We did a session recently, and we were listening to one planner who said something incredible.

She said when a client walks in who’s got a pension with some of the big consulting actuaries, she now genuinely stops and thinks about whether it’s worth taking that client on at all. Because the experience of extracting the money and data from those firms – and I think we all know who we’re talking about – is so bad that actually, the experience for the client will be terrible, it will jam her firm up, and it won’t be economical for her to serve that client.

She described how there will be this moment where a client has gone through an initial financial planning process which he or she enjoys very much indeed, and then the industry turns up and goes: “Alright, how you doing? We’d just like to slow everything down a bit if that’s alright.” So suddenly the promise of the firm is dashed by the actions of the industry. This rule is designed to stop that.

What you can expect of providers

The great thing that has happened over the last 15 years or so is that advisers have moved into the driving seat. You are closest to the client, so therefore you are in control.

There is more control flowing through planning firms and advisory firms than there ever has been. So when it comes to your supply chain, which is what you’re putting together in order to deliver good client outcomes, you can ask providers to do things.

You can ask them for data they don’t give you at the moment. You can ask them for justifications for things, you can ask them to run tests for you, you can ask for lots and lots of things.

But the framework around Consumer Duty puts tension into it. So providers can ask things of you as well, because they can’t manufacture properly if they don’t understand what it is you’re doing and how you’re doing it.

So we’ve got two groups meant to be holding each other to account, requiring things of each other (mainly data, I think) that allow both parties to make better business decisions. Now, while there’ll be some arguments around that, I think that sounds kind of wonderful. But I also think we’re a very long way away from that right now.

The jeopardy of client comms

I have a fundamental concern in all of this, which is the issue of communications with clients.

A lot of this isn’t advisers’ fault. It has to do with the absolute barrage of mince that most providers chuck at you, which by the way has got nothing to do with legal or compliance requirements. It has everything to do with ass-covering, added to over years and years and years. So the challenge is on for the providers you work with, because they’re going to have to strip a lot of that stuff back.

You simply cannot give somebody a 95-page Ts and Cs document and go: “There you are mate, this is fine.” Because the client can’t possibly make an informed judgment based on that.

The counterargument is people sign up to 300 pages of terms when they use a Kindle. Yet the two aren’t really comparable. If I have a disappointing experience with my Kindle, I may not enjoy reading my e-book. If I don’t get it right for my retirement, I’m entirely screwed. So the jeopardy that goes alongside that is material, the impacts are material, and therefore the work that’s needed is material.

You are in control of what your clients receive, which is an interesting concept.

That is to say if you put them into an arrangement where you know a provider will give them materials which they cannot possibly be expected to read and use to make good decisions, my argument would be that at least in the spirit of the duty, you just failed. You must not act in a way that gets in the way of suitability. And the suitability resides in those four outcomes. This is the area I’m most worried about.

Our suitability template

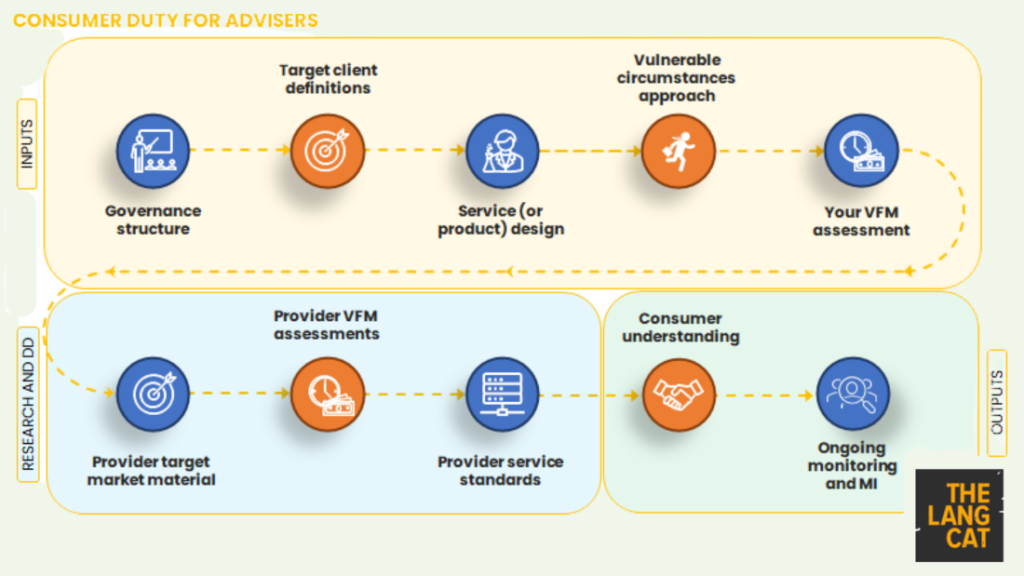

Concentrating on the adviser inputs along the top, the first thing is to have your governance structure worked out. How will your business be set up to ensure that somebody is on the hook for this? If you’re a very small firm, it’s obviously you. If you’re a larger firm, somebody needs to have that hat to wear.

That person needs to have a seat at the table and to be able to challenge you. There needs to be a culture of challenge inside businesses that allows the voice of the consumer to come through.

Next is target client definitions – if you haven’t done them, get them done. Then it’s service or product design. If you’re an adviser clearly you’re not designing products, but you are designing services. So you need to write down what those are, what it is you actually do and what you offer, and that will vary from firm to firm.

This is the kind of thing you think it’s going to be simple, but it’s much, much harder when you actually sit down with a blank sheet of paper.

There’s a thing about vulnerability as well. If you read the actual Consumer Duty papers, you’ll see quite a lot in there. And then value for money assessments. Now that’s a session in itself. I’m not going to dwell on what I think goes into value, but you need to write down whether you think what you’re doing for clients in terms of your own charging, and the stuff that you expose them to, is good value for money.

What Consumer Duty is really all about

There’s a lot in Consumer Duty, and not all of it is immediately obvious. We’re going to find out lots more about it over the next year or two.

It’s about suitability, and the concept of generating and ensuring ongoing suitability not just for the destination, but for the journey as well. Getting all those little points of detail right is, to me, the fundamental building block of ensuring that the duty isn’t a pain in the ass.

I’ve heard many people say this is just something else they have to deal with. I don’t think it should be. I think there’s some good stuff in here. I’m sure there’ll be nonsense as well, but that doesn’t matter because there’s always nonsense everywhere. My in-laws are farmers and things like ear tags and forms and so on get them very cross.

Every industry has this stuff. You can own the parts of it that enable you to better serve clients and create better outcomes for them by getting suitability right. This session was just designed to try and get you thinking about some of that.

—

This article is based on a talk given by Mark at the PFS Festival of Financial Planning 2022.