So there’s no getting around it: when you look at the findings in our latest Advice Gap report, they don’t exactly paint a great picture when it comes to accessing advice and planning.

Some headline stats to illustrate the point:

- 9% of consumers paid for advice in the past two years, down from 11% in 2023

- 55% of adviser respondents have already stopped serving clients as a result of Consumer Duty

- Compared to last year, more advice firms are saying if a potential client came to them with £20,000 to invest they would either turn them away or only work with them subject to certain criteria.

(Based on research with YouGov with over 2,000 UK consumers and research we carried out with 291 advice professionals.)

At our launch event in London earlier this month, we discussed tackling the advice gap from a consumer perspective, the role of tech and explored the potential solutions to get more financial help to the people that need it.

Our panellists were:

- Claire Walsh, chartered financial planner, Dartington Wealth Management

- Jamie Jenkins, director of policy and communications, Royal London

- Jenny Davidson, commercial proposition director, Quilter

- Laura Purkess, consumer features editor and consumer champion, The Sun

Sizing up the problem

It wasn’t all doom and gloom in the report though. Over 90% of clients who have paid for advice found it helpful. Also, trust is no longer the biggest barrier to paying for advice – instead it’s about being persuaded that advice would save consumers money.

Quilter commercial proposition director Jenny Davidson said: “It’s really interesting that trust in financial advice is actually increasing and Consumer Duty is a catalyst for that.

“There’s quite a lot of positivity all the way through the report, but as an industry, it’s clear we need to grapple with the advice gap and drive forward the right outcomes for the customer.”

In her role at The Sun, Laura Purkess is confronted with the advice gap in the kinds of personal finance issues readers come to her with. Sometimes these will be “Amazon didn’t deliver my parcel”, but often these are more complicated, such as wanting support with a complex DB pension.

She said: “The main problem is the lack of awareness. People don’t write to me because they don’t want to see an adviser, but because they don’t know they could see an adviser, or how to access one. And probably [in any event], they couldn’t see an adviser because they don’t have enough money. But it’s still a lot of money to them.”

Laura said the upshot is people end up turning to Google for help with their pensions. Unfortunately, what tends to come top of the listings isn’t advice firms or Pension Wise but unregulated businesses, claims firms or scammers – “all the kinds of places we don’t want people going to first.”

Royal London director of policy and communications Jamie Jenkins made the comparison between getting a survey when buying a house, and the need for financial advice.

He said: “There is a parallel in that some people will be making decisions around their finances without the use of an adviser, and carrying out transactions that are potentially of a similar magnitude as buying a house.

“That’s not to say that the figure of 9% of people taking advice should be 100%. But for those at a point in their lives when advice becomes an actual need, I suspect that figure is greater than 9%.”

A question of cost, and other barriers

Dartington Wealth Management chartered financial planner Claire Walsh said there is a perception problem with advice and financial services versus other ‘cooler’ resources out there.

She said: “Within the industry, we’re a bit hamstrung in terms of how we can promote regulated financial advice and products.

“Increasingly we’re seeing the rise of ‘alternatives’: things like cryptocurrency, crowdfunding and even gambling.

“For younger people, there are all these other ways of dealing with their money. Traditional products and providers can look quite staid and dull in comparison.”

The cost of advice, largely driven by the regulatory demands placed on advice firms, also remains a deterrent.

This is something Laura sees too.

“Where people can’t see a tangible outcome [of paying for advice], they just see a figure and panic. Even people with quite a lot of money, if they don’t know what they are going to get and what their ‘return on investment’ is going to be, then they are put off.”

Capacity to serve

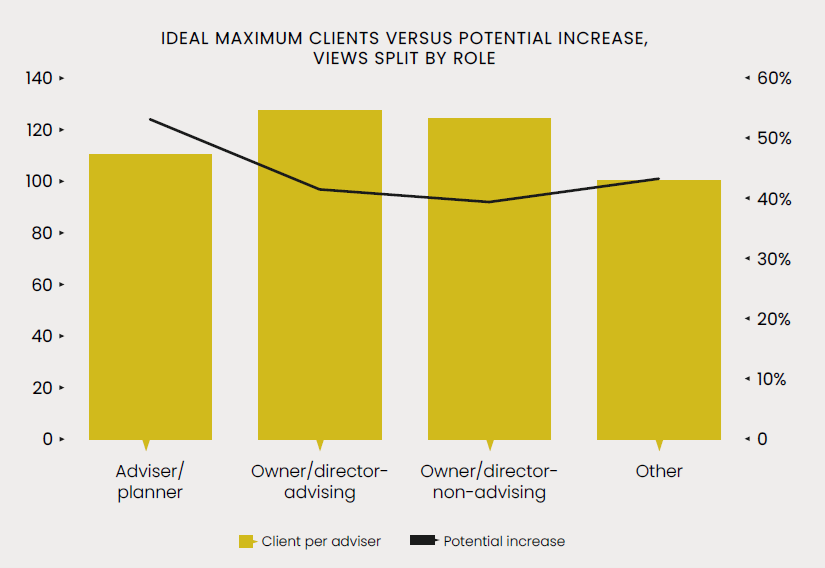

One of the areas we looked at as part of our adviser research was what firms thought was the ideal number of clients per adviser, and what that could increase to in a ‘nirvana’ state where everything worked as it should.

The ideal average came at between 100 and 120 clients per adviser, with the potential to increase capacity by as much as 40 to 50%.

When we split this according to role, those in purely adviser and planner roles are more likely to understand the impact of battling inefficient tech and processes on their ability to serve more clients.

On the question of how many clients advisers could serve in future, particularly in light of better tech integration, Jamie argued there are things in train already that could make a difference to current sluggish processes.

“We underestimate the impact of the pensions dashboard… this is actually the digitalisation of pensions.”

The way forward

It is difficult to persuade people about the value of advice and planning for their financial future when they don’t know the difference it can make.

For Claire, she takes it back to how she herself began to relate to financial services.

“What piqued my interest in finance in the first place was the idea of making my money work harder for me, and that I could become wealthy not just through my day job.

“We see that now through the so-called ‘finfluencers’ on social media, and the FIRE movement (financial independence retire early). A lot more people at younger ages are thinking: ‘Hang on a minute, how can I make this work for me?’”

She believes engaging people starts with communicating in a way that will grab their attention, whether that’s examples of how much to put into your pension based on the age you’re starting, or case studies with people explaining how advice or investing has worked for them.

Laura agrees: “People don’t know what they don’t know. So it’s all well and good telling them they can look up advice about their pension, but I encounter people who don’t even know they’ve got a pension.”

Laura said financial education in schools needs to go much further, explaining concepts such as pensions and mortgages.

“Anything [to do with finance] you’re going to encounter in your working life needs to be addressed as early as possible, and it’s not. People coming to The Sun at age 40 and reading something about a pension, and that’s the first place they ever read about it. I mean, that’s horrifying really, isn’t it?”

Jenny suggested employers could be “hugely powerful” in getting employees to understand the basics of pension contributions, savings, mortgages and protection.

She noted the level of industry conversation around the FCA’s advice guidance boundary review, and especially the targeted support model of ‘people like you’ take this action.

Jenny said there needs to be greater clarity around providing a helpful nudge versus what consumers think they’re getting. That is, will they think are receiving advice when they’re not?

Yet despite this, she is broadly supportive of the proposals.

Quilter is carrying out work with a behavioural consultant to look in more detail at targeted support, and consumer psychology and behaviour as part of that.

She said: “Targeted support is all about making people better informed, so I think it will actually help… people understand in a tangible way what it could mean for them.

“There’s absolutely a will around targeted support in the industry. I think it will help to close the advice gap. It’s really about providing support, and we’re all responsible for that.

“That does mean we have to now collectively move forward and agree that is the outcome we want to achieve for the end customer.”

Jamie said the reality is that unadvised customers are struggling with what they should be doing at a practical level.

For example, providers can tell people 8% pension contributions aren’t likely to be enough, that a 10% withdrawal rate is too high, and that cash won’t keep pace with inflation.

But if someone asks ‘what should I do then?’, providers can’t give a meaningful answer.

He said: “Our industry has developed this kind of mentality of telling people what they shouldn’t do… Where targeted support fits is we start to become helpful. People make better decisions, and at some point they seek out advice.

“If providers interpret targeted support as an opportunity to sell products, then it’s missing the point entirely. It’s about helping people.”

—

Looking for more Advice Gap insight?

The report is free to download thanks to our sponsors: Royal London, Quilter, abrdn and Fidelity International.